Memories of Roast Beef, Mashed Potatoes & Peas

Remembering the magic of Ed’s Warehouse Restaurants … all six of them

“If you like home cooking, eat at home.”

That was the slogan of Ed’s Warehouse Restaurant when it opened on January 20, 1966. Like many of the slogans that Ed Mirvish used to promote Honest Ed’s, the legendary bargain department store that first brought him to prominence, the slogan for his first restaurant was self-deprecating and fun. But it was also accurate.

After Ed bought, saved from demolition, and restored the Royal Alexandra Theatre on King Street in 1963, he realized that there were two important things he still had to do: make the theatre operational 52 weeks a year, and create an exciting neighbourhood around it. The first was a matter of finding enough worthwhile shows to put on the stage of the Royal Alex; the second was a little more difficult.

The King Street neighbourhood was more or less derelict throughout most of the 1950s and into the 1960s. Across the street from the theatre were disused railway yards and around it were empty warehouse buildings, abandoned by businesses that had moved to the suburbs to avoid the downtown taxes. Ed knew that in order to attract a large enough audience to fill his theatre he needed something more around the beautiful heritage theatre on which he had lavished a million dollars to restore.

What kind of business is complementary to the theatre business? A place to have a meal before the show, of course.

So Ed bought “the large but rather homely six-storey building next door,” as he explained in his introduction to the souvenir magazine, “Deluxe Guide in Living Colour to Ed’s Warehouse Restaurants,” which was available at the restaurants in the late 1970s. The building had been used as a dry goods warehouse and a printing business. For $525,000, Ed got the building and floors of old furniture, publishers’ stock and printing presses.

His idea was to open a “joint,” by which he meant a restaurant that would be fun to visit. He set out to recreate one of his favourite restaurants, Durgin-Park in Faneuil Hall Marketplace in downtown Boston, which he described as “a century-old, rough-and-tumble truck-drivers tavern, where burly guys in visored caps plunk down at long tables and sink their shoes in the sawdust on the floor.”

That was the initial idea, but it didn’t quite turn out that way.

Ed would be the first to tell you that he knew nothing about restaurants, just like he knew nothing about theatres when he bought the Royal Alex. But he would also tell you “sheer ignorance beats experience.” He also believed “you can’t succeed if you don’t try” and “listen to your instincts and follow your convictions.” (By the way, these are some of the rules and lessons he espoused in his bestselling memoir, How to Build An Empire on an Orange Crate, or 121 Lessons I Never Learned in School [Key Porter Books, 1993]).

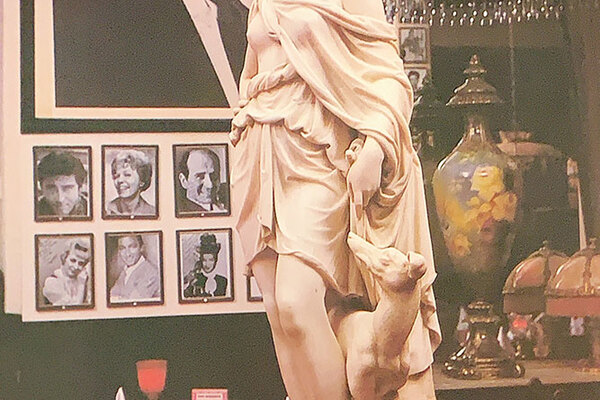

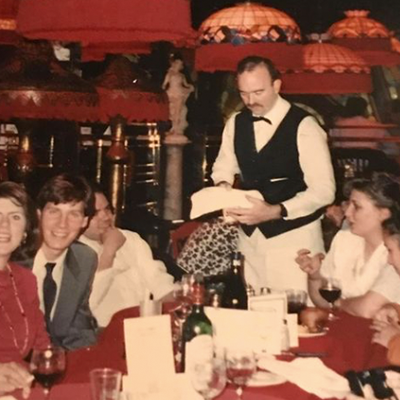

Ed consulted with successful restaurateurs and with experienced interior designers and other professionals. But what they suggested sounded too traditional and boring. He decided to do it his way and the result was a 150-seat dining room on the west side of the first floor of the warehouse building. He used the crew of carpenters, electricians and construction workers that looked after Honest Ed’s. To outfit it, he bought furnishings from auction sales and antique stores (he bought the entire stock of one dealer), stained-glass windows from demolished buildings, Tiffany lampshades with red fringes, even elaborate brass doors and railings from stately old bank buildings that were being “modernised.” Anything that would dazzle the eye and create conversation. To connect the dining room with the Royal Alex next door, framed photos of the stars who had played at the theatre since 1907 hung on the wooden pillars and walls of the room. The colour palette was red, gold and more red. The final effect was “Baroque bordello,” as one wisecracking journalist described it when the joint first opened.

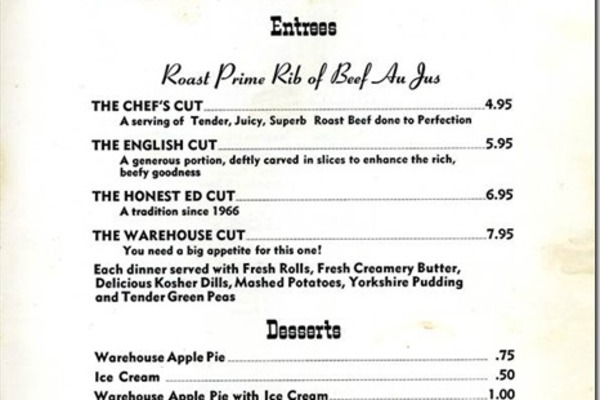

On the menu was only one item, a dish that wasn’t often cooked at home because of the time and preparation it took, but one that could be served in mere minutes so that theatregoers could still enjoy their meal and not be late for the show: roast prime rib of beef. Truth in advertising — “If you like home cooking, eat at home.”

Ed called the joint Ed’s Warehouse, because it was on the first floor of a warehouse and it was created by Ed. More truth in advertising.

In 1966, a meal of roast beef, with rolls and butter, kosher dills, mashed potatoes, peas and Yorkshire pudding, cost only $3.15 at Ed’s Warehouse. Great value.

The joint caught on immediately. Lineups to get in were common. So Ed expanded into the east side of the first floor, then onto the second floor and then the basement. When Ed turned 64 he decided to buy the building farther west on King Street, a former brass foundry, and opened Old Ed’s, in honour of his “senior years.” Then he bought the building next to that.

Along with all these extensions, the choices on the menu also grew. But they were never overwhelming, at least not for food. Ed believed in keeping it simple. Still, he would often joke that his menu had two pages of food and 10 pages of cocktails, liquor, beer and wine.

By the 1970s, there were six restaurants: Ed’s Warehouse, Ed’s World-Famous Italian, Ed’s Folly, Old Ed’s, Honourable Ed’s Chinese and Ed’s Seafood. But you could get his famous roast prime rib of beef at all of them.

The restaurants served more than 1.2 million meals annually, consisting of: 250,000 pounds of potatoes, 250,000 pounds of peas, 1 million pounds of beef, 500,000 Yorkshire puddings and 3 million dinner rolls. On Saturday nights alone, 6,000 diners would be served.

Ed’s restaurants became a destination. Young couples had first dates at one of Ed’s restaurants, married couples went to celebrate anniversaries, families marked special occasions, companies held employee banquets. Together with the bustling Royal Alex, Ed’s restaurants made King Street the happening neighbourhood in the city.

There’s nothing like imitation to prove something is a success, and that’s what happened with Ed’s restaurants. The first major restaurant that wasn't connected with Ed to open in the reinvigorated neighbourhood was Filet of Sole, which opened in a smaller warehouse building at Duncan and Pearl streets in 1984. It used the same formula that Ed created: good food at great value in a fun atmosphere. Then Kit Kat opened in a row house on King just west of John. That was the start of Restaurant Row.

At the same time, the rail yards across from the Royal Alex became Roy Thomson Hall and the MetroCentre. At Wellington and John, other yards became the new CBC headquarters, and farther down the street the SkyDome was built. A few years later, in 1993, the Mirvish family built the Princess of Wales Theatre. It was then that the neighbourhood was officially named the Entertainment District.

By that point, there were more restaurants in the Entertainment District than in another area in Toronto. The place that had begun it all, Ed’s Warehouse, seemed to no longer be necessary. After all, Ed had only opened his restaurants to help bring audiences to his theatre. That had been accomplished a thousand times over.

In the late 1990s, Ed started winding down his restaurants. The first to go was Ed’s Seafood, then Ed’s Italian, Ed’s Folly and Ed’s Warehouse. On September 16, 2000, the last of the restaurants, Old’s Ed’s, closed.

Peter Dekker was the head bartender for all of Ed’s restaurants for 25 of the 31 years he worked there. He started at Ed’s Warehouse in 1969 and was among the very last employees to see the last restaurant closed.

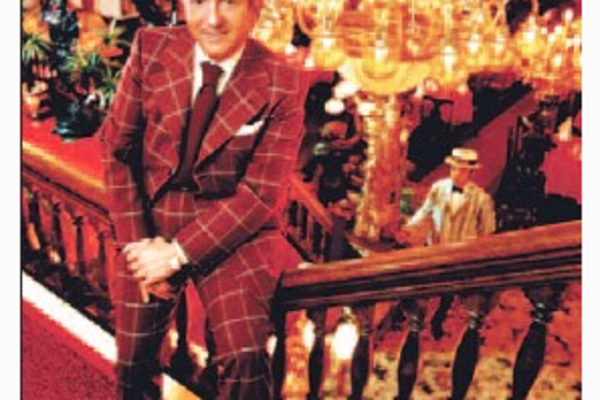

“I always believed Ed had the golden touch,” he recently said. “He was really a showman and the restaurants were his stage set, and I believe he loved every moment of being on his stage. Even though he was a shy guy, when he was playing the part of Ed the entrepreneur, he shined.

"Like clockwork he would arrive each day at noon at the restaurants from having spent the morning working at Honest Ed's. He would say hello to all the staff and listen to all the news from the various managers. Then he would go into one of the dining rooms. He was there to greet guests but never imposed himself on them. He would then have a light lunch, usually with his son or a business acquaintance. If there was a matinee at one of the theatres, he would go check it out.”

Peter says Ed’s desire to please people and his attention to detail were the two qualities that made him successful.

“He loved people, all kinds of people, and they loved him. You could see how excited some people were to go up to him for a chat, and he was just as excited to talk with them and find out about their lives.

“I especially liked it when Ed had celebrities for dinner. Liberace was always the most fun. Every time he came to Ed’s Warehouse, all the other diners would stand and applaud. Of course, it was impossible not to notice him when he walked in.

“Tony Bennett, Lena Horne, Pierre Trudeau, Wayne Gretzky, so many people I can’t remember all of them. If there was a celebrity in town, Ed would have them for dinner. He and his wife Annie were always the most gracious hosts.

“I remember the times John Candy came for dinner. He would order two of the Warehouse cuts of prime rib. These were the biggest cuts on the menu. But first he’d have soup and salad. Sometimes he’d have two desserts. But he’d only have one Diet Coke and nothing else to drink. I still find that funny.

“Working at Ed’s restaurants was always exciting. In the very busy years, you never had a minute to take a breath. In two hours of the dinner rush before the curtain went up at the theatre I’d have to mix more than 600 cocktails, all by hand. In later years, I convinced Yale Simpson, who managed all the restaurants for Ed, to bring in electric mixing machines. That saved a lot of time. No more shaking and shaking until my arms felt as if they were going to fall off.

“People in those days drank much more than they do today. We had a special Ed’s martini — eight ounces of pure alcohol. Even at lunch people would have three or four of them. I could never figure out how they could even stand after drinking that much. But it was a different time, different attitudes. People didn’t always do the best for their bodies and health.

“I came to Canada from Holland and I’ve always loved how this country had been made by so many people from so many different places. Ed’s restaurants were just like Canada. The staff represented almost every continent on the globe. It was a huge staff, probably more than 300 people. And most of us who worked there stayed there our entire careers. That says something about the places doesn’t it?

“When Old Ed’s closed it was the end of an era. And it was time for me to retire. I’d had a great time.”